The SPECIAL ANNIVERSARY SECTION is available in PRINT ONLY.

To real all the related stories, see the many pictures and enjoy the congratulatory messages, get the full October 2025. Order it online (go to the “Get RePlay” tab, select “Sample Copies” and put October 2025 in the notes) or call 818-776-2880.

50 Years at RePlay Magazine

Witness to a Half-Century of Coin-op Entertainment

With the publication of this issue, RePlay Magazine turns 50 years of age. The anniversary marks a half century serving the jukebox and amusement machine industry with a trade journal aimed at the people who either make, sell or place amusement and music machines in game rooms and in single sites; the industry itself has been on the map for well over 100 years.

RePlay was founded by Eddie Adlum, a New Yorker who came to the task after 11 years producing the Coin Machine section at Cash Box Magazine. He left that music industry publication in August of 1975 and within two months, launched the brand new monthly he called RePlay, which has become a fixture in the business now generally referred to as “coin-op.”

In fact, during RePlay’s earliest days, the business was literally coin-operated whereas in today’s world, a huge portion of the machines on location accept paper money or cards. The method of printing RePlay or any other publication has also changed with the times, from the photo offset process using negative film to today’s digital system enabling the magazine to print in Pontiac, Ill., (rather than “down the street” in the Los Angeles area where the stories and other elements of the magazine are assembled).

“We now send the book to the printer over the internet rather than on the back seat of my car,” says Eddie, who remains its publisher at age 86. (His phrase, “the book,” is magazine talk for the product itself.)

Eddie’s original vision was to produce a magazine that reported developments (large and small) in the business. He was warned that there wasn’t enough going on in coin-op, nor enough companies making machines, to support it with advertising. The crystal ball would have shown them wrong.

Those five decades have been the most dynamic in the entire history of coin-op. The number of manufacturers exploded during that time, especially during the dawn of the video game and the more recent domination of the game center business by prize redemption machines.

Over the years, the games got bigger (albeit more expensive) while the makeup of the market shifted a good bit from the route owners to the arcade people, including those in FECs (family entertainment centers) which themselves exploded in more recent times. The number of machine wholesalers which coin-op calls “distributors” has drastically downsized to several large networks, leaving only a handful of independent dealers compared to 50 years ago.

RePlay itself became the only American trade magazine in print that dedicates itself to covering coin-op after the departure of Play Meter. Vending Times, which had a coin-machine section, is no longer in print. RePlay has survived and prospered despite economic setbacks like the Great Recession and the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as “competition” from the internet. “People like the convenience of a magazine they can read, put down, pick up again any time they like,” says Eddie.

Ron Gold, the late Cleveland operator-distributor, called RePlay: “Our industry at work and at play.” Besides reporting on new machines entering the market and how well the games perform in the cash box on its Players’ Choice charts, RePlay reports on coin-op’s other activities like any other business publication. As it says on its front cover, it is “America’s Amusement Machine Monthly.”

In the Beginning

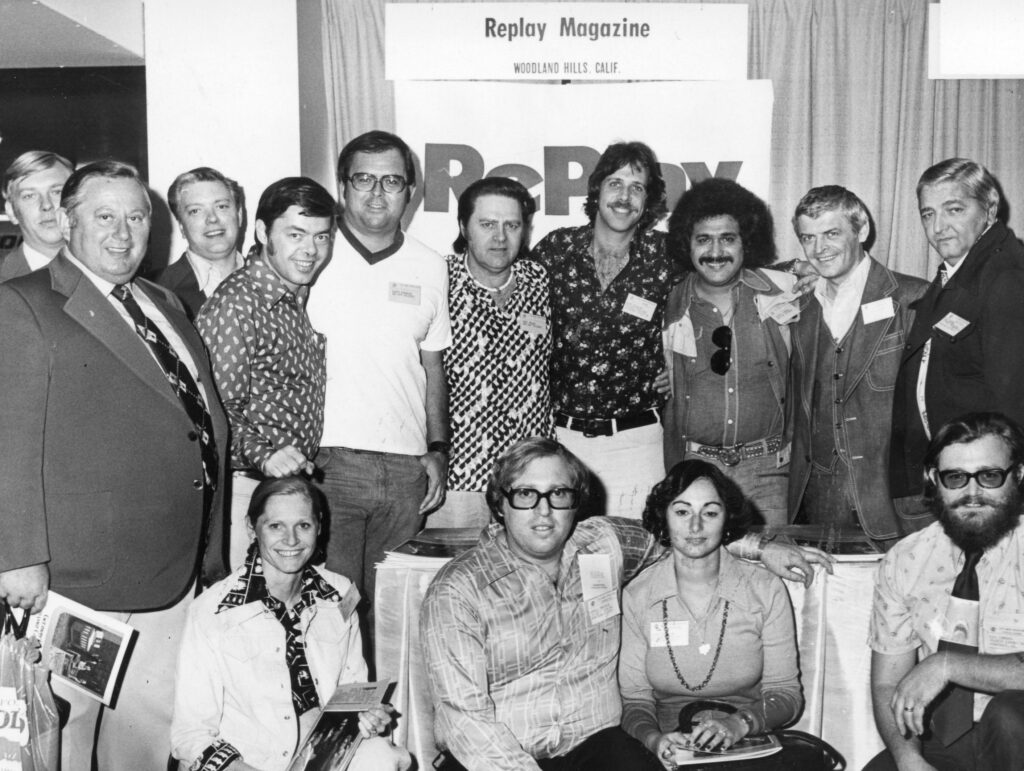

Eddie and his then-wife Tippy incorporated RePlay Publishing Inc. in the state of California in mid-October of 1975 and distributed their very first edition at that year’s MOA Exposition at the Conrad Hilton Hotel in Chicago. A free exhibit booth was offered to the Adlums by MOA’s executive director Fred Granger who, following Bob Blundred, was only that association’s second full-time administrator. Along with his assistant Bonnie York, Granger was the face of MOA for many years.

“MOA” stood for Music Operators of America and had served as the U.S. association of jukebox route operators since 1949 when it was formed to protect its members from paying performing royalties to writers of the songs played on the machines. (The group was successful in that endeavor until the spring of 1985 when an $8 per jukebox fee was set by a U.S. Congressional Committee.)

The fee went up steadily in successive years and was finally “disrupted” by the appearance of digital jukeboxes with “built in” royalties initially introduced by a Canadian-born company called TouchTunes. But back when RePlay was launched, the industry was generally called the “jukebox business” and its staples were defined as the “3 Ps” (phonographs, pinballs and pool); if “cigarette machine” began with a P, that would have made for 4 Ps.

The market leader was Seeburg phonographs, followed in no special order by Rowe AMI, Rock-Ola and NSM. American Wurlitzer had already pulled the plug on jukebox manufacture a year before. Today, only TouchTunes and AMI remain making the vast number of music machines going into U.S. locations. The music itself comes through the internet rather than from 45 rpm records (or later, CDs), hence the disappearance of many “one-stops” from the map).

It was a great time to bow a new coin-op magazine, and with over a decade of experience in making publications earned at Cash Box, Eddie thought he might be the man to do it.

Following the 1974 AMOA show in Chicago, Eddie brought the idea of a separate publication strictly on coin-op to Cash Box owner George Albert.

“I was all fired up from what I saw at the show,” Eddie remembers. “A guy in New Orleans named Ralph Lally who had worked for an operator down there named Tac Elms had distributed a sample of his new magazine Play Meter and I heard opportunity pounding on our door. Well, George turned my idea down saying the coin machine section in his record business magazine was too important to his record advertisers to change anything,” Eddie said.

Games Take the Lead

This 1975 “MOA show” as it was routinely called by trade people, was a watershed event in trade history, and not because RePlay had shown up (and was very much welcomed by showgoers who signed up for subscriptions). It was a singular show because the games side of the industry was finally recognized for its preeminence in the trade over the music machine. Why?

Because a new game builder called Atari had made the earth tremble two years earlier with a machine called Pong and a series of follow up “video games” (as they came to be called) that came right on top of the hugely popular electronic pinball machines popularized by Bally.

It was back-to-back “booms” that fed cash boxes with record earnings built almost totally on quarters. As such, the powers that ran the MOA decided to put an “A” for “Amusement” in front of “Music,” and an industry often called the “jukebox business” eventually became the “video game business.”

History would show that an explosion in the entertainment world was about to happen and shove the record business into the corner as video game play became the way young people spent their leisure dollars, or in our case, quarters. Actually, all anyone had to do was look at Japan where many local stores had turned themselves into arcades to take advantage of the moment.

“During my years at Cash Box, I’d learned ‘how to put ink on paper,’ as we say. Gathering stories, selling ads, dummying-up pages … all the things the printer needed and how to make all that happen. That was my hands-on education at George Albert’s place,” Eddie advised.

“I already knew how to write because I had a degree in journalism from Fordham back in my hometown of the Bronx where one of the instructors said I had a flair for story telling but that I should get a dictionary and learn how to spell,” Eddie remembers with a grin. “When the computer showed up, I put that dictionary on the shelf,” he added.

So, knowing how to dot the Is and cross the Ts in magazine production, and funded by personal savings plus help from coin-op friends like Philadelphia’s Al Rodstein and New York State’s Millie McCarthy, Eddie and Tippy tossed the dice and RePlay came out swinging. Besides, after 11 years covering coin-op for Cash Box, he already knew the people who “turned the wheels” in the industry, often on a personal basis. Translation: a publisher’s 3 P’s … the printer, the paper merchant and the post office … all had to be paid, and you did that by getting ads.

Roll the Presses!

Their first cover featured Dot Records’ artist Freddy Fender, who had a chart topper called Wasted Days and Wasted Nights at the time. “I got San Diego operators Bill and Dot Worthy to set up a Wurlitzer and had Freddy sit on it … but I didn’t tell him to lay his lit cigarette on it, too. You can see it when you look at the cover,” Eddie says.

You can’t talk about the life of a business magazine without talking about its industry’s evolution at the same time, and the amusement machine business had indeed exploded during the late ’70s, especially when a Taito game called Space Invaders hit the market in 1978.

“We’d only been putting RePlay out a couple of years at the time from our home in L.A. and later in an office about a mile away,” said Eddie. “Two guys from Cash Box had come aboard, Beau Eurell who did the record section and Bert Bogash who wrote some stories and generally helped here and there. Most the advertising we got came from record labels touting new singles.

“Well, at the 1978 Chicago show, I was touring the exhibits taking pictures of people and machines when I got to the Midway booth where my pal Larry Berke was demonstrating a couple of new games for showgoers.

“‘What have you got, Larry?’ I asked. ‘Well, a bunch of stuff like this one we licensed from Taito,’ he said, pointing at Space Invaders. ‘The operators seem to like it a lot,’ he added. They liked it so much that before the dust had settled years later, that singular machine had sold around 300,000 units worldwide, knockoffs included,” Eddie advised.

That record still holds, though you can’t turn your nose down on later “hits” of this “video boom” like the Pac-Man/Ms. Pac-Man combo with 200,000 machines sold and Nintendo’s Donkey Kong with around 67,000. Note that all three of these games were developed in Japan. Other Japanese games, now “classics” like Namco’s Galaga as well as Atari’s Pole Position and the Steve Jobs/Steve Wozniac-designed Breakout, captured the world’s imagination to the detriment of other forms of entertainment.

The coin-op games business had truly exploded. At its peak, market observers said that the money going into video games was larger than what the record industry and motion picture business earned combined. Something like that wasn’t lost on opportunity seekers, who jumped into manufacturing games and especially others who put them out on the street or created whole new arcades. Before this gravy train drove off the tracks, games had appeared in such places as Chinese restaurants and even funeral homes.

Everybody seemed to want a piece of the action. Loads of part-timers like firemen and police officers hit distribution offices and signed paper to get games. A lot of distributors wrote gobs of orders but later paid the price of extended credit when play finally wore off in the early ’80s and wannabe operators simply took a powder.

Newcomers = Newgoers

During the boom, however, the AMOA’s operator membership swelled, as did RePlay’s subscriptions. The association’s fall trade shows looked like rush hour at New York’s Grand Central Station, so many (like 8,000) would show up to see the new games. While out on the streets of America, numerous know-nothing “operators” spoiled things, to the annoyance of the more established route owners. Some “newbies” offered excessive location commissions, polluting the waters for the veterans. Too many cooks, too many bad deals. Two new expositions were created to exploit the action, one by RePlay’s competitor Play Meter (the AOE show) and a new association of manufacturers now called the AAMA (the ASI expo). Play Meter ended up suing the manufacturers association for conspiracy to destroy their AOE show but both parties ultimately shook hands by joining together in the spring’s American Coin Machine Exposition (ACME). It changed names back to ASI some 10 years later.

Then, the once-dominant AMOA show held each fall was eventually eclipsed by the ever-growing fall IAAPA (originally the Parks and Pools show) and merged with ASI to create the Amusement Expo International we have today. The schedule of trade shows these days is simply the IAAPA in fall, the AEI in the spring, and a spread of local association annual affairs where manufacturers come to promote their new goods.

During those “glory days” of the ’70s and ’80s for electronic pinball and video game sales, Bally … once considered an also-ran among the product lines distributors vied for … had become the #1 brand in flipper games as well as videos via its Midway division. But sales weren’t so hot for companies making anything else, like jukeboxes and pool tables.

Valley, then as now the venerable pool table line, hired a Brunswick veteran named Chuck Milhem to find a way to improve their sales. Along with prominent Minnesota route operator Dick Hawkins (D&R/Star), they launched the Valley National 8-Ball Assn. (VNEA). While it certainly helped Valley sales, what it really did was create the most enduring tournament program at the location level this industry has ever seen.

Tournaments for electronic dart players sponsored by Arachnid (BullShooter) and even the AMOA itself (NDA) are active today along with independent programs on darts, pins, air hockey and even foosballs run by various operators and associations. When play on video fell off, these promotions went far to bring up the slack in the cash box while also helping locations like neighborhood bars improve their own bottom lines.

Various other attempts to fill the video collection void were tried with various degrees of success, like laserdisc games (the exception being Dragon’s Lair), movie jukeboxes, video software-flip systems like Neo-Geo and Nintendo’s VS., payphones (forget about it), and early VR (thanks but not nearly as ready as it is today).

Proving video games as a class was hardly dead, two folks from Strata Games named Elaine and Richard Ditton came out with a game called Golden Tee Golf, branded “Incredible Technologies,” 40 years ago that would go on to make incredible collections through its many iterations. There were other good videos as well, like Data East’s Kung Fu games and Capcom Bowling to consider. Of course, what Raw Thrills does with video these days doesn’t need mention. They and their Play Mechanix partners set the bar for the state of that artform.

Oh, yes. There was one more solution to falling collections. The dollar coin. After years of lobbying Congress to make one, they did, but the public not only turned its back on the “Susie” (called that for its likeness of Susan B. Anthony), it hardly ever looked at it in the first place (not like in Canada where their “Loonie” was and is roundly accepted).

Enter Redemption

What ultimately did fill that void was (and remains) ticket redemption games. Once actually illegal because they gave winners a “thing of value,” cranes and rotaries and literally hundreds of games which, like Skee-Ball, shot out tickets were exactly what players wanted and which now occupy the number one slot among game room operators from the income standpoint.

Redemption also spawned a sub-business among the prize manufacturers who showed up to fill that slot. There are even some games whose prizes are more tickets themselves! (Thanks, Smart Industries!) It also pounded home the credo that “winners make players” to operators who screwed around with percentaging.

There are always problems to face and during all these years, a good number came, and thankfully, went. Parallel video game boards imported from Japan turned out to infringe American subsidiaries of the very Japanese companies that made them in the first place. These, plus out-and-out counterfeit boards occupied the attention of the AAMA and others like the FBI throughout the ’90s.

There were other problems, like parents comparing some of the games to gambling devices and others calling games like Mortal Kombat “disgusting” due to the gore it displayed on the monitor. Hard to argue that last one, but it sure made money if you didn’t mind making it that way (the game was far more graphic that the old Exidy Death Race which suffered the same bad publicity).

Gary Stern never lost faith making the industry’s most inventive game – pinball – but many others did, especially after being eclipsed by the video game revolution. Even Bally Pinball exited the flipper arena. Stern, however, has had the last laugh on skeptics and can now point to a flourishing pinball business which includes competition from Jack Guarnieri (Jersey Jack), American Pinball and some others.

Newer classes of novelty games that came and stayed post-video, include punching bags and basketball cages which did their fair share keeping the operator’s lights on. Besides early video uprights, there are classics among redemption machines still making money on location, like Stacker and Cyclone (the latter sprang from Buffalo’s prolific ICE which wasn’t around when RePlay first hit the stands).

Today, almost all the Japanese game makers are gone, replaced by new companies that cut their spurs in redemption like Bay Tek, Benchmark, Coastal, Smart, Team Play and others. With the exception of I.T.’s perpetual hit Golden Tee Golf, the upright video cabinet has been largely replaced by deluxe attractions from the likes of Raw Thrills, LAI, Bandai Namco and Sega.

Winding it Up

Dozens of people have worked for RePlay over these 50 years, including full-timers, as well as part-timers who labored at the company’s book bindery, which RePlay cobbled together when it became difficult to find a dependable “perfect bindery” in the Los Angeles area. Once a month, all staffers turned out to get “the book” together at this “bindery in a garage” and into the mail every month for years. Eddie loved what he called “the brainless work.” Everyone else hated it.

“We had some talented people working here along the way, like Dave Stroud who landed at Cinematronics and later with his own dealership in the San Diego market called Progressive Games,” Eddie recalls. “We had Marcus Webb as our editor for years, a very bright guy. Then Steve White took over Marcus’ job, later attending law school at night. Steve now works as an attorney in Portland, Oregon.

“But there are two people I’ll call close friends rather than just employees – Key Snodgress and Barry Zweben – and there’s my daughter Ingrid Milkes. “There really is no way RePlay would be RePlay or really even exist if it wasn’t for these three,” Eddie insists. “Along with our talented, nation-hopping Matt Harding helping Key with the story side of the book, we have Barry getting the ads and Ingrid running subscriptions and mail fulfillment. She also does the charts.”

Curiously, both Key and Barry joined the RePlay staff way back in the same month of June 1981. Eddie’s daughter, Ingrid, has really worked there since the beginning when her parents put her to work mailing sample records to jukebox operators for Columbia and Epic Records.

“I guess we broke the child labor laws, but Ingrid and her younger brother Kenny had fun doing that job,” remembers Eddie. “At least I hope they did,” he added. (One of the records they mailed was After the Loving by Engelbert Humperdinck.)

Eddie himself still works part-time doing desk work, while keeping himself available whenever anyone needs his help or asks a question needing a long-timer’s memory to answer.

“I never figured this project would last this long. Publishing isn’t the easiest business to get into and keep going,” he says today. “I just wish old Sol Tabb and my friends from the beginning like Al Kress were still around to see this,” Eddie added.